Artistic performance and photography: relations and interconnections

Maria Elisa Dainelli

Articles

Artistic performance and photography have always shared a deep bond, both constituting the support of the other, and mutually transforming themselves into a single becoming as well. The purpose of this article is to identify some categories of interaction between these two artistic forms, in order to better understand the influences and the mutual interaction’s nodes.

We are going to refer to a practice, present in Western countries, that began around the 1960s as artistic performance, which consists in the staging of programmed actions, with the aim of transmitting a message to the public[1]. The means of expression that can be included in the performance category are infinite but we can assert that the body plays a central role as the vehicle for artistic languages[2]. In this context, photography becomes both the documentation and the narration of an action[3].

Let’s start from the first category and see how, in some art staging, photography has acted as the execution’s visual representation.

Shunk-Kender[4] photographers, for example, had the opportunity to follow Yves Klein’s work, documenting both his Saut dans le vide, from 1960, and the performance Anthropometry, also from 1960, in which the artist had painted images by using women’s bodies. At this point, documenting art meant, for both the photographer and the artist, establishing a close relationship of collaboration, in which the work of art took on a second life, acquired that durability over time, otherwise denied. In fact, photography, with its role of documentation, gives eternity to the performance, allows it to be archived and, why not, museumizing it through possible exhibitions.

The artist

therefore establishes a symbiotic relationship with the photographer in which

his art corresponds to a visual representation: two perspectives that meet in

one. In this regard, we recall the photograph by Babette Mangolte, from 1973, Woman

walking down a Ladder, which portrays the dancer Trisha Brown intent on

walking on some structures in a perfectly perpendicular position (effect

obtained through the use of some ropes, to which she was tied with). The

partnership between the two of them gave rise to various researches.

In other cases, however, photography, from researches, becomes the only possibility of narrating the performance. This is the case of Eikoh Hosoe’s photographs: he had taken some of the dancer Tatsumi Hijikata, in 1969. They have the role of freezing the movement and making a staging of still moments possible in which the Katamaitachi, a dance invented by Hijikata himself, is blocked in the context in which it is performed. It all becomes a monument to the dance and to the eye of the photographer who introduces it to the viewer. The dancer is represented in all his strength, in the action and effort to make his body the fulcrum of a becoming in which the presence of the subject merges with the surrounding environment. A performance that almost recalls today’s flash mobs, in which, however, only the perfection of movement is the subject of photography.

Continuing among the infinite examples present in the world of contemporary art, we cannot fail to turn to the play of roles, identity and performance that make the self-portrait the preferred way of expression.

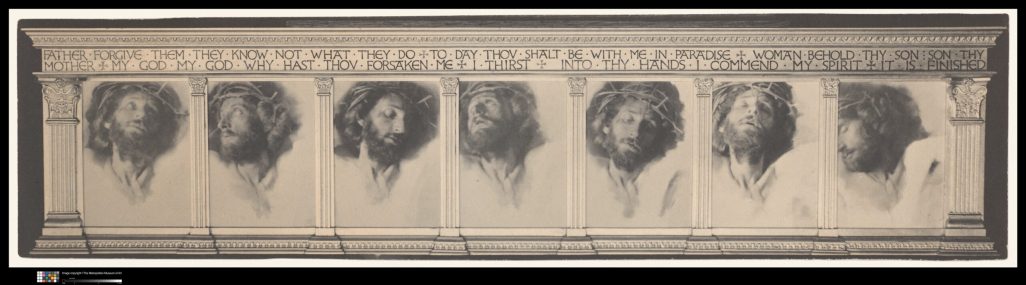

Stages such as those of Fred Holland Day, who wanted to represent the life of Christ in seven photos (Seven last words of Christ), in 1898, approaching the camera in an extremely contemporary way, are an example. These harsh images, which earned him considerable criticism, represent some of the examples of the early days of self-portrait.

In other cases, however, photography, from researches, becomes the only possibility of narrating the performance. This is the case of Eikoh Hosoe’s photographs: he had taken some of the dancer Tatsumi Hijikata, in 1969. They have the role of freezing the movement and making a staging of still moments possible in which the Katamaitachi, a dance invented by Hijikata himself, is blocked in the context in which it is performed. It all becomes a monument to the dance and to the eye of the photographer who introduces it to the viewer. The dancer is represented in all his strength, in the action and effort to make his body the fulcrum of a becoming in which the presence of the subject merges with the surrounding environment. A performance that almost recalls today’s flash mobs, in which, however, only the perfection of movement is the subject of photography.

Continuing among the infinite examples present in the world of contemporary art, we cannot fail to turn to the play of roles, identity and performance that make the self-portrait the preferred way of expression.

Stages such as those of Fred Holland Day, who wanted to represent the life of Christ in seven photos (Seven last words of Christ), in 1898, approaching the camera in an extremely contemporary way, are an example. These harsh images, which earned him considerable criticism, represent some of the examples of the early days of self-portrait.A second example comes from a photographer well known for her self-portraits of her: Cindy Sherman. The work that made her famous and which was bought by the MOMA in New York in 1995 for over a million dollars is Untitled Film Stills, a series inspired by the B movies of the 1950s. There are 62 black and white images, taken between 1969 and 1980, in which many of the themes dear to her are already presented: disguise, a representation of the stereotypes imposed on women and interpreted by making them a parody, the media imaginaries of the time . Her photographs can be considered both documentation of a performance and artistic and photographic expression on their own. The feminist world has criticized her for perpetrating a macho imaginary of the woman’s body, to which she has always replied to follow her taste for disguise and the interpretation of characters: a performative act that wants to be an autonomous, independent language. and free from further interpretations and messages. We therefore come to the contemporary panorama. You started Amalia Ulman’s Excellences & Perfections project in 2014. Using Instagram as a platform for disseminating her selfies, the artist collected a series of images with the aim of including user reactions within the performance. Amalia has in fact collected the comments of her followers, noting how the responses to photographs that portrayed her semi-naked were much harder than the others that portrayed her in everyday life scenes. Performing a gesture with real anthropomorphising features[5], the young woman changed her body, gaining weight, losing weight, changing the colour of her hair, etc., in order to interpret characters and imitate others (including, for example, Kim Kardashian). The project, organized according to a climax, aims to investigate the different stereotypes fed by the system of social networks. Hence, immediacy becomes a distinctive trait of the relationship between photography and performance, up to and including, in fact, the immediate reactions of the viewers. In a standardized world, where everyone can express their opinion through special platforms, the performance becomes a social experiment and it seems almost impossible to do it without a third party: the spectator.